Compositional Methodologies (2)

Approaching a commission: sketching, refining and learning how to stop (beginning)

This is the second in a short series of articles focusing on sharing a range of my compositional methodologies and approaches, seen through the lens of a recent commission for the University of Leeds. In the third post coming next week, I’m looking forward to sharing a recording of the actual piece with you.

In last weeks’ post, I wrote extensively about the early stages of a working on a commission; moving forward from the position of being approached and everything agreed on, to actually beginning the process of developing the work: exploring, finding inspiration, and delving deep into the heart of the subject matter - in this case, a long-form piano piece responding to an exhibition at the University of Leeds of artworks by Manchester-based artist Mary Griffiths.

For additional context, and for those who may have missed it, here is last weeks’ post:

Before I share with you the full recording of the piece in its entirety next week (you’ve got to eek these things out, you know!) I thought it would be helpful, and, I hope, interesting, to show you how the composition “looked” (and there’s plenty more to unpack in this phraseology another time) at the moment I sat down to perform it.

The exhibition features a range of Mary’s captivating works which are highly distinctive in terms of their visual features, the materials and process employed in their creation, and the aesthetics and meaning they convey.

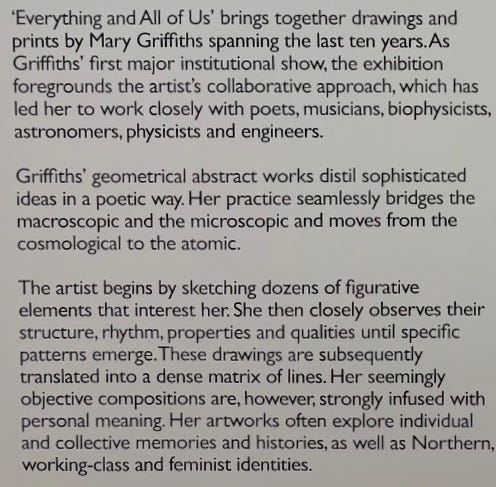

The introductory text on entrance to the gallery reads as follows:

There was so much which captivated me just from these few paragraphs, but the thing which stood out the most was: ‘her works take a long time to complete, and, in turn, also demand and repay slow looking’.

In receipt of a generously open brief, I chose to narrow the focus of my commission to a response to just one - though mightily substantial - artwork from Mary’s Everything And All Of Us exhibition, shown thus:

This magnificent, beautiful wall-drawing is titled Prophet and was created through a painstaking process which involves applying layer upon layer of graphite onto a plasterboard surface. This is then burnished to a highly reflective smooth sheen, before the geometric lines and figures are meticulously etched into the surface.

Prophet is a collaborative work, born as the result of an extensive series of conversations with Tony Crowley, a Professor of English at University of Leeds, with whom Griffiths shared a similar yet unknown-at-the-time childhood as children of the Irish Catholic diaspora in working-class Liverpool.

Memory forms an essential theme across both their work, and notably in Prophet, finding a unanimity in this work through the link to place and representation. In the exhibition catalogue, Crowley eloquently describes the work in the following way:

When I visited the gallery for the first time, it was Prophet which stood out so much to me, almost like it was inviting me in to Mary’s work and world. Despite its imposing size coupled with the rich, deep, darkness of the graphite (which was also paradoxically reflective…whaaaaaat?!) surface, it never felt threatening; in contrast, it feels welcoming, not least by the fact, as a commission, it was made as a response to the architecture of the space in which it sits.

It wasn’t simply something which I found to be “nice”; it was head-turning and attention-grabbing by its size, scope, scale, breadth and depth.

And so, having been surfeited of the context of the subject matter, let me now show you how I aimed to convey some of the meaning of, and my musical response to, this outstanding piece of art.

Approaches

Before I had played a note, I sat down and had a very good, long think. I know this sounds obvious, but I’m sure I can’t be the only one who just wants to crack on, trying things out, whilst not having much of an idea or plan, and I touched more on this last week.

Something about this project felt different to the range of similar things I had done before. Firstly, there wasn’t much time - by the time things were all agreed, I would have two months to make a piece of up to 20 minutes long, and this time period contained the busy Christmas and New Year season, and some time away in Europe on tour.

Secondly, as it was to be performed at the very end of the six-month exhibition duration, there was a hard deadline in place, as opposed to other projects which have often been subject to last-minute changes.

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, I had determined to focus my composition specifically on Prophet, which would be situated immediately to the left of the piano as I performed; literally in its shadow. This meant the source material/inspiration for the piece was going to be constantly on view for the audience as they listened; in some ways creating a collaborative interactivity of art forms - one static and complete, the other still coming into existence.

Almost like taking the form of an homage to Mary’s creative practice and process itself, the music needed to be layered, burnished and inscribed into being in real-time, as if mirroring the process by which it was made.

This created an initial sense of dilemma. We are often taught that books and films - at least by linearly-normative narrative design - should have easily comprehendible structures: a beginning, middle and end, or to be closely aligned to Todorov’s Theory, and as a great deal of music often follows similarly structural norms, in the context of crafting a compositional commission, it can feel very much like one has to have something thoroughly mapped out and composed to the nth degree.

On this occasion, though, I sensed and knew there was only going to be one approach I could take - to aim to be much freer than I usually would be; to be less beholden to a score; to allow for a great deal more improvisation than I would ever usually give myself for something like this; and to try to reference the layering, burnishing and etching element of Mary’s practice.

But…this was pretty scary. Anytime you step away from the comfort zone of your regular process is daunting, but especially so when it is a paid commission, and the artist herself is going to be at the performance!

I was also aware due to the time constraints, my schedule and my change in circumstances at home, that I would have less opportunity to be fully immersed in this task, as perhaps I might have had chance to in years gone by. I would need to be able to generally work quicker, and likely in more frequent, less-lengthy time periods. As such, these parameters would be an important part of how I approached this commission.

Process: Sketching

Whenever someone asks me about my composition process, and my answer references how I often tend to loosely sketch out ideas in a manuscript book, I’ll have a quiet chuckle to myself inside. Sketching is an important part of an artist/painters’ oeuvre, and I often wonder if people ever assume there is anything remotely approaching an artistic element to my sketching of musical ideas. The humour comes in knowing just how atrocious I am at anything artistic/drawing/painting-related - essentially anything which requires an additional implement.

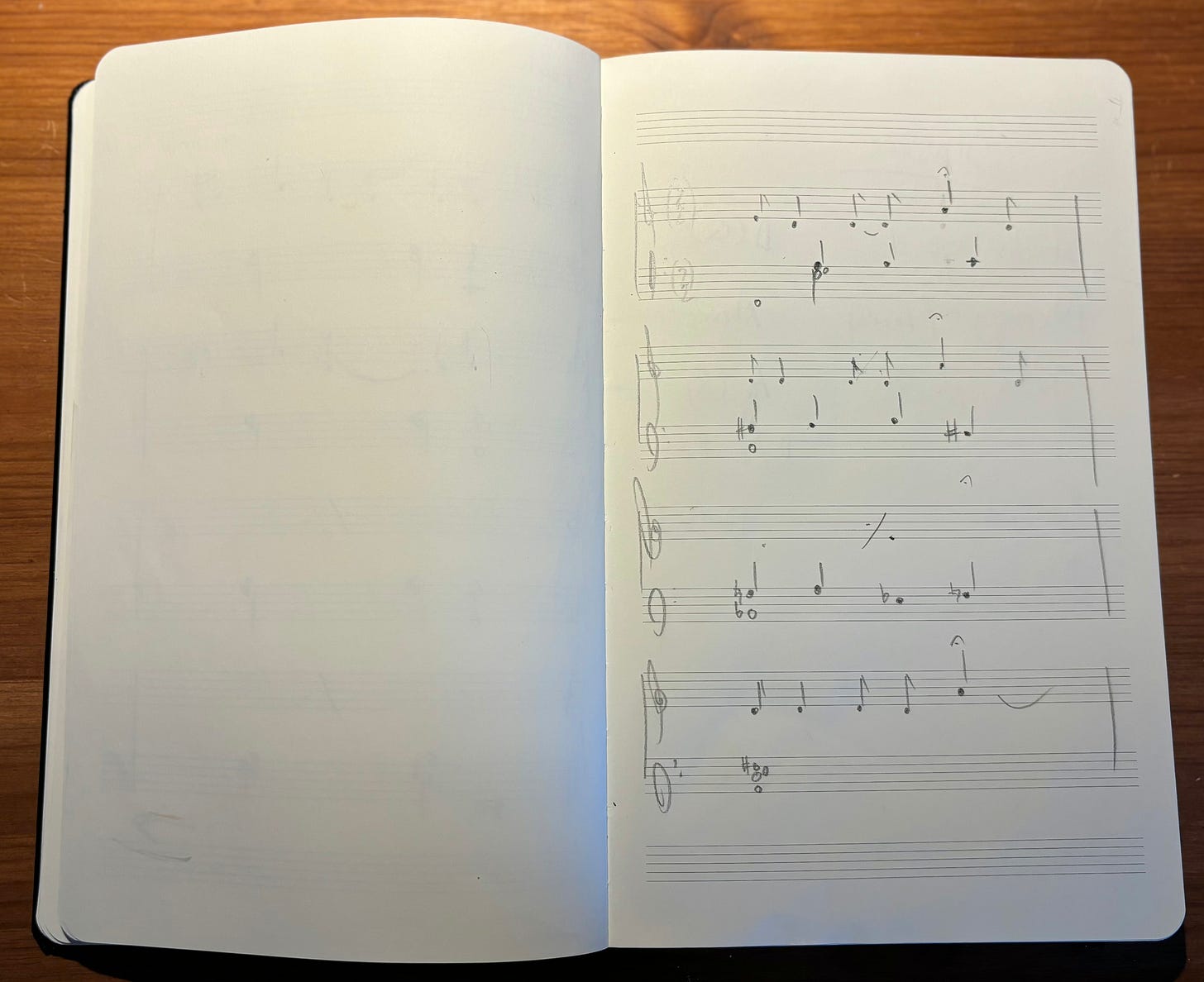

My piano students often complain my handwriting is illegible (although come on, guys, we all know the How To Get Out Of Piano Practice manual), and often I look back over my musical/score sketches and cringe at its lack of clarity or complete untidiness.

Whilst I wouldn’t be the first composer to be afflicted in this way, mentioning it does at least slightly assuage my fears of showing you my sketches for this project, for which it is entirely necessary for the entire purpose of this post.

So, why sketch?

I very much appreciate how sketching ideas out onto manuscript gives me a certain sense of freedom. Aside from the obvious aspect of getting ideas down on paper as soon as possible so as to not forget them, I appreciate feeling that something hasn’t been or isn’t finished, and that the ideas put to paper represent but a range of points on the compositional spectrum: from initial starting points to more defined, thought-out ideas - all the while allowing for a degree of openness and flexibility within the music and both its interpretation and development.

It’s fair to say this philosophy is a key element to my compositional practice, neatly summed up as: not wanting to be too tied down. At least, at not too early a stage.

I have often found, and continue to find, the notion of thinking about a piece of music (at the compositional stage) in the vein of determining “this is the way it goes now” to be a little unsatisfactory and a barrier to further exploration and refinement.

The continuum stretching from a fully composed scored piece played exactly as written, through to sketched musical systems, scales, motifs and ideas acting as a basis for improvisation is wide and long, with plenty of space inbetween.

I find sketching ideas, loosely - mostly in lovely A4 Leuchtturm manuscript books - with a rubbered pencil, to be a helpful approach as I explore and experiment with a range of ideas. It helps avoid the pitfall of assuming that the first idea you have will be the best one you have/the one you use (although, ironically, it is fun when this happens), whilst remembering how we feel about and in ourselves on any given day can have a distinct impact on our work, it being something of an expression of who we are.

That said, this approach belies something of a tension within me, perhaps even demonstrating a wider, emblematic challenge at the heart of music-making and composition:

What makes a good idea good?

Process: Refining

Well, there’s a question for the ages. Stand down Plato; move over Aristotle. Don’t worry, I’ve got it covered from here.

I know I’ve got a good idea when I want to play it again. It’s not as simple as just making a catchy melody, but if I absent-mindedly hum or sing it back to myself later, that’s a decent sign; even more so if I can remember how to play it the following day without looking at the sketch or listening to the voice memo - also an important tool as part of the “sketching” process.

(side note: if music is primarily a fundamentally auditory experience, why is the act of composers writing things down so venerated and exalted as “the way to do it”?)

Of course, the question ‘what makes a good idea good’ could be worded in a multiplicity of ways so as to provoke all manner of responses, but what if we flipped the meaning a little so it read…

What helps a good idea become better?

If you came here looking for the answer to a different question - ‘how to make a good idea better’ - you’re out of luck. Anything promising a quick fix or the “correct way to do things” is likely a hoax, my friends. Read all the creativity books going, speak to your creative friends, garner as much as you can from podcasts and other practitioners; but even dear Julia Cameron, as legendary as she is, won’t have the exact approaches we ourselves need.

We have to do the work. Sure, we take from others - gladly and gratefully - what we can glean and apply it to our context through the lens of our approach and philosophy; but we have to do the work.

A good idea becomes better when it has the freedom and space to breathe, giving it and us the opportunity to explore many of the options which open up; simultaneously finding a way to be non-committal, whilst also be able and ready to say (and I can only apologise in advance for this): ‘fuck it, this will do’.

I hope the message is clear: occasionally the first idea is good, fits perfectly and its job done (hurray!). However, just as the layer-upon-layer of graphite in Mary’s work is beautiful in and of itself from a tonal and textural perspective, when it has been extensively burnished with a range of materials, it takes on a new life of its own; still the same form, but literally gleaming, helping us to see it in a whole different light.

Let’s Get Geeky

It’s high time we delved deeper into the actual work. As always, I will try to tread a fine music theory line, with the awareness that whilst some of you are well-versed in musical lingo, others may approach it with less theoretical knowledge but with just as equal passion and engaged interest. There must be a place for everyone.

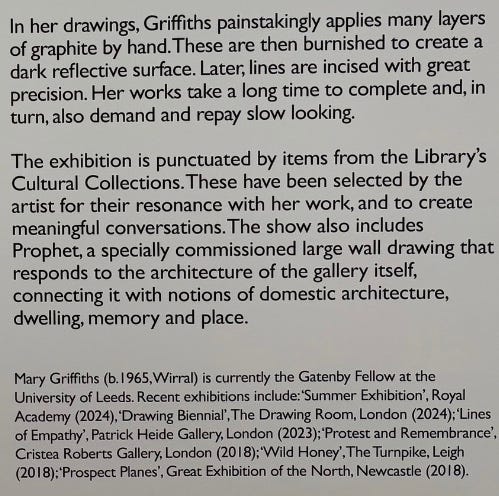

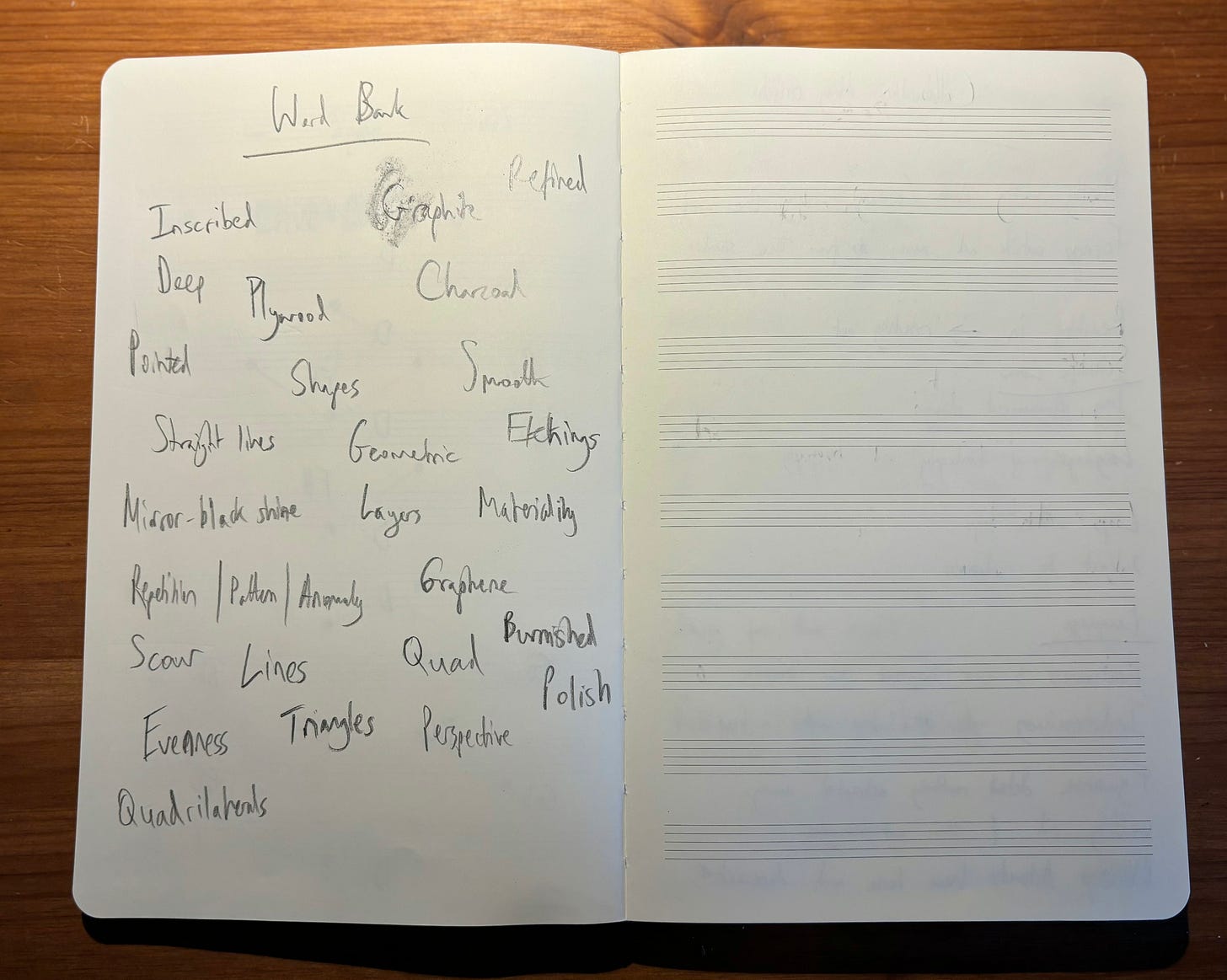

One of the things I like to do when approaching something like this is to dump as many words which spring to mind about the project or subject as I possibly can onto the page, to use them as inspiration, and to focus my mind around certain topics which leap off the page.

The following photo shows my notes from a conversational Q&A with Mary and a number of her fellow collaborators…

I have always found words and writing to be stimulating and inspirational, but it is only fairly recently where I have come to realise how essential they are in my practice. I’ve written previously about my approach to titling works with one word, but it is certainly a little deeper than just doing a brainstorm/mindmap/wordbank.

A focus on words and writing helps me to develop narratives around which to anchor musical ideas; encourages me to look for deeper meanings around etymologies and linguistics; and ensures a sense of clarity and focus on the task when buffeted by constant distractions.

I chose to centre my long-form piece around responding to Mary’s astounding work, Prophet, which is how I chose, in turn, to title my piece. Here it is, in situ, in the Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery in the University of Leeds’ iconic Parkinson Building, where the performance would take place…

I decided it would make most sense to break my piece up into four distinct sections (if you would like to call them movements, I won’t stop you), which each represent a specific aspect of the thematic influences and expressions which Prophet portrays:

Language

Memory

Process

Something else I never quite managed to name

- - -

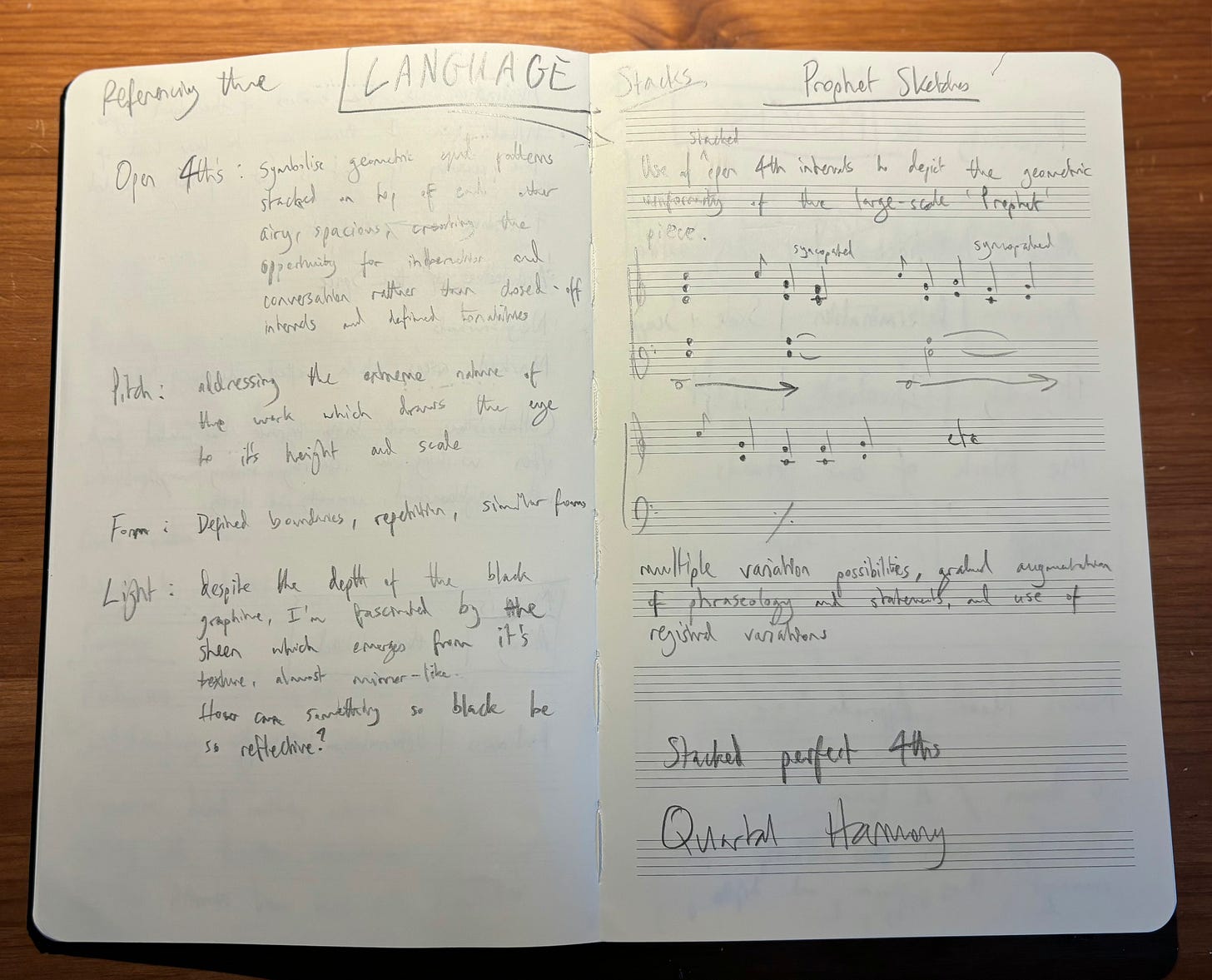

STACKS

The first section of my piece is titled Stacks. If you gaze back at the Prophet wall-drawing, you’ll see how the etched, inscribed lines are meticulously equal, to the millimetre.

I found the visuality of this work particularly striking, and I immediately thought of the horizontal lines as referencing piano strings. Whilst the piano obviously has its own distinct pattern/spacing of white and black notes centred around equal temperament, the uniformity of the width of the spaces between the lines drew my attention to this aspect of the piano too.

In more general terms, the height and scale of the work made me think in relation to pitch and the way that the piano has more breadth and scope than any other instrument from a registral perspective.

I sought to reference the equal geometric lines of the artwork in the music by using an almost exclusively quartal harmonic language, which is where chords (clusters of notes) are created using perfect fourth intervals (the distance between notes), rather than the chords and harmonic language we are often most used to hearing across the majority of musical genres which tend to employ chords using notes in intervals of thirds (technically two notes apart, i.e. C-E).

These perfect fourths are stacked one on top of the other to create wide, spacious, resonant harmonic voicings placed across almost two octaves. This language is used in this instance as a means of “not giving much away”, easing the listener into a new sound and visual world, and to give the impression of a sense of dialogue between the artwork and the music.

These quartal chords are accompanied by low pedal notes, with a nominal tonal centre focused around D, although these do change, creating further blending of notes together.

Whilst there is an element of syncopation in the rhythmical aspect of Stacks, it is broadly quite a spacious, uncluttered beginning to the piece overall. The intention here is to try and capture the feelings I felt when walking into the gallery for the first time and seeing the wall-drawing in front of me.

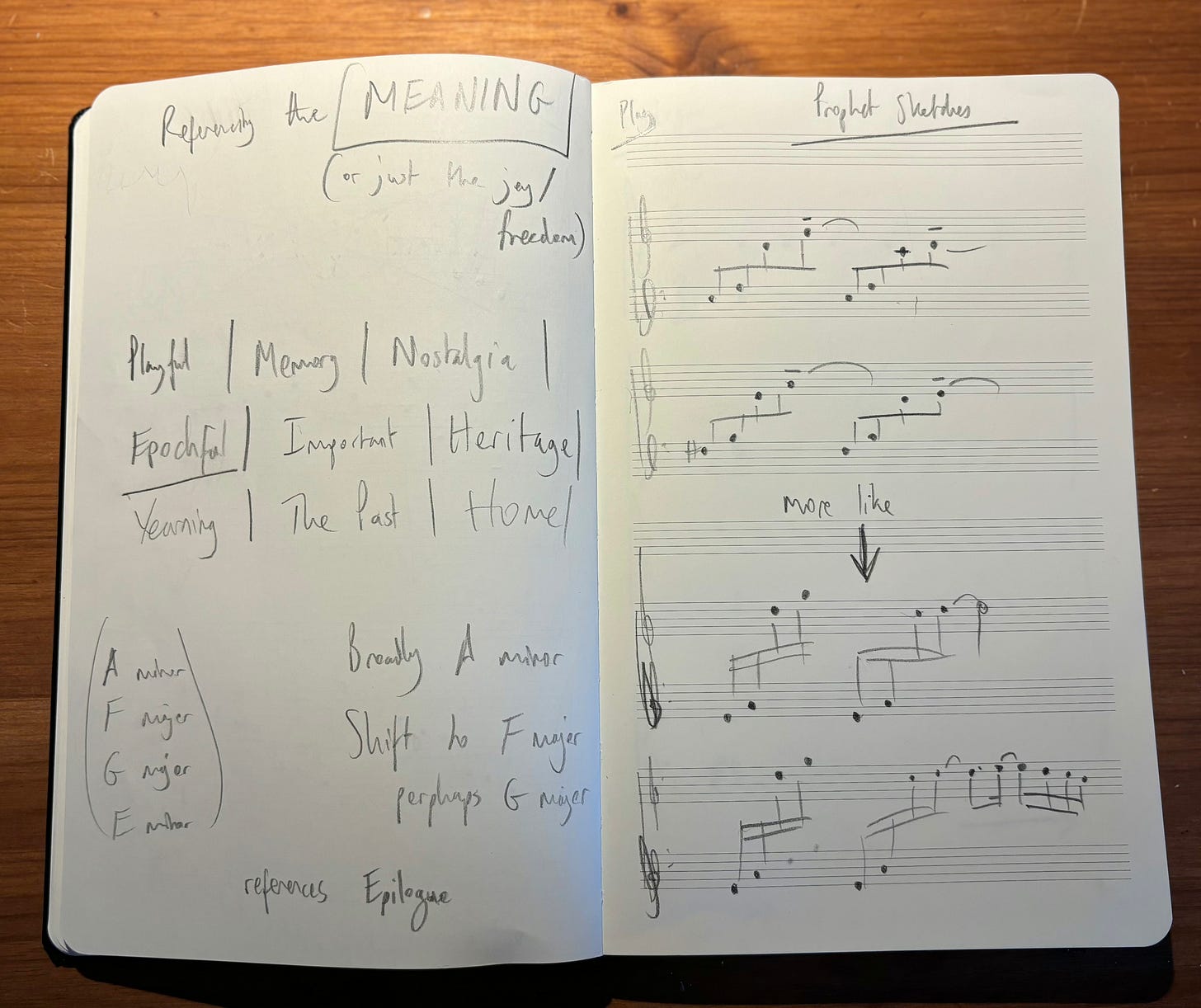

RECALL

The second section of the piece refers to the memory aspect of Mary and Tony’s conversations and collaborations. Bonding over shared memories of similar childhood experiences and environments in working-class Liverpool played a vital role in helping bring this work into being.

The musical systems I created for this section are extremely simple, but, I think, very effective in creating a sense of nostalgia and memory of home. Based around two repetitive quaver runs broken across the hands and staves, in the exact centre of the piano.

The notes used are uncomplicated, making slight reference to the quartal nature of STACKS (because the language we use and adopt is clearly going to be highly influenced by wherever home was or is), but broadening the out its scope to create a tonal centre around A minor.

Mary mentioned this section created an especially cinematic feeling and emotion for her. The way in which its repetitiveness creates familiarity, whilst rhythmically continues to push and pull throughout, echoing that feeling of heartstrings being pulled for a certain place, moment in time, person/people, or specific location.

It attempts to recreate the sensation we can experience when a rush of memories come flooding back all at once, often because of something triggering it. There can be a pleasantness and enjoyment in this version of feeling overwhelmed, in that we can quickly be taken back to periods in our life which have such resonance, importance and consequence.

STACKS pt. 2

Before the piece moves towards its apex - aiming to be a celebration of Mary’s process and what is made as a result - I decided to include a reprise of STACKS.

This was mainly because our memories do not always occur in a linear way, as if by magic creating a compelling narrative plot line for our own lives.

The following section is going to be the most musically involved part of the piece from every angle, so it helps to take an additional breath (and to remember to slow down).

However this reprise is all transposed (a technique where the pitch of a phrase is shifted to make it sound higher or lower) up by an interval of a perfect 5th. This version is higher in pitch and feels a little less warm than when previously stated.

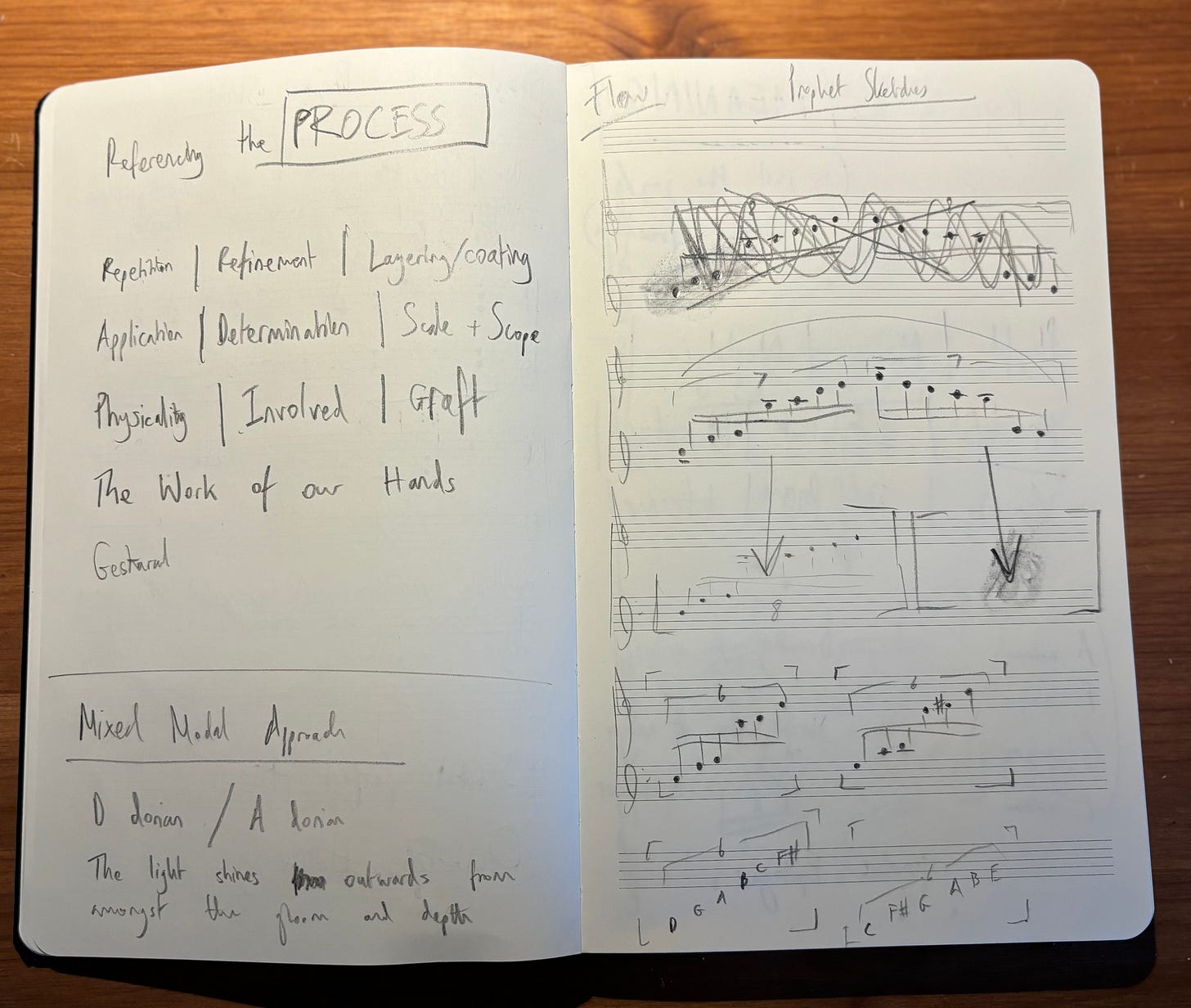

PROCESS

I mentioned previously how taken I was with the way Mary approaches her work - its not just a methodology, but one which values slowness and taking ones time.

However, as I spoke more with her about her process, and indeed spent time in the gallery gazing into the deep dark of the graphite surface, the more I came to realised just how intense, time-consuming and physical this approach to making art is.

From my sketches below, you can certainly see what I was attempting to do - a collection of very quickly played notes (for which I decided on septuplets) with the aim of creating and demonstrating a hive of activity based around repetitive actions.

Alongside trying to help the audience to hear this as a reflection on Mary’s practice, I also hoped to draw attention to the way that the musical system I used bubbles and gurgles upwards from a specific note-centre to then fall away again, as quickly as it came.

There are a number of note series used in PROCESS which create an element of ambiguity, not least around the tonal centre, with the use of an F# allowing for a different sound altogether as an A dorian scale begins to take hold as the nominal tonal centre.

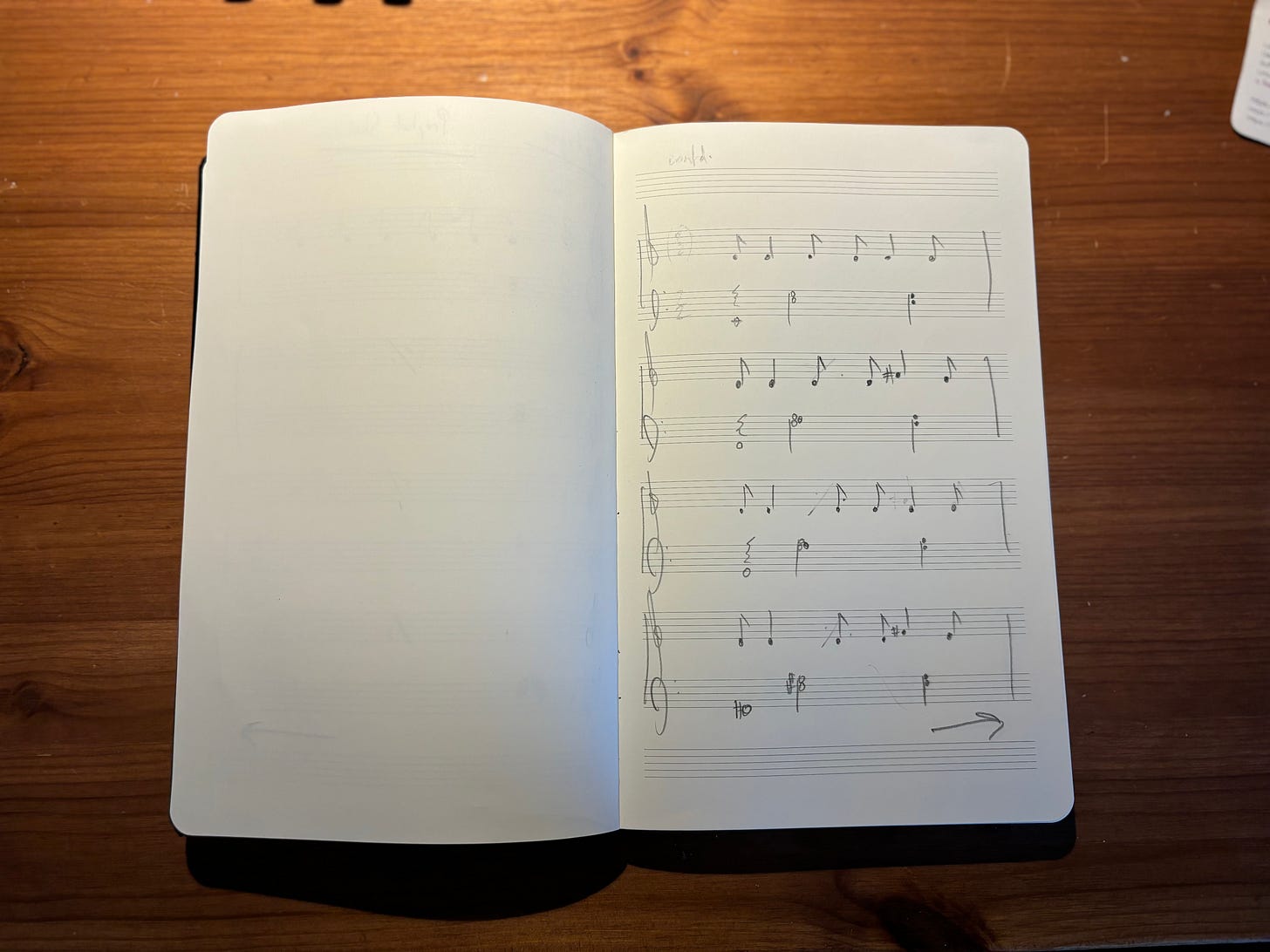

EPILOGUE

The rationale behind this final section of music, is of course to help a natural and satisfactory conclusion of sorts emerge. However, I felt it needed to be done in a way which was stately, strong and profound - the work exists; great effort and lengths have been gone to achieve it, and it remains really quite stark and bold as a piece of artwork.

I attempt to do this with a repetitive syncopated phrase in which only one note is repeated again and again, before a few additional notes create more of melodic theme to latch on to. This melody - essentially in D major - functions in contrast to the broader harmonic movement in which both sharps contained in D major are naturalised, creating a sense of tension as notes clash, creating mild dissonances.

It feels like the piece ends in a similarly conversational way, the dialogue happening this time between a simple right-hand melody and left-hand chords punctuating the rhythmical gaps.

Learning How To Stop (Beginning)

I know what you are thinking. At least, I think I do.

How do the sketches above translate into a long-form piece of music?

It’s a fair question, and one I would have asked myself not too long ago. Perhaps this demonstrates a development/change in my practice, or perhaps less transformational but no less consequential, maybe I am becoming more confident in my ability to compose “in the moment”.

As I discussed earlier, the continuum between composition and improvisation is in many ways a false one - each informs the other, and it is not just jazz where improvisation is allowed to happen. In this instance, I worked very hard on creating short musical systems which would allow for a distinctive voice to be heard, and to be able to use them in a range of different ways.

In the first post of this series, I finished by thinking through the process of learning how to begin. Again, the semantics are important here. It’s not a ‘here’s how to begin’ manual - the learning is deliberately a present tense activity because I don’t think we ever stop learning (and I certainly never want to arrive).

Just as important, though - and arguably more important - is learning how to stop. I think it is universally understood that a creatives’ greatest challenge is how to know when I have finished, and with good reason. The refining process could, in theory, continue for ever, and nothing would ever be done, finished or “good enough”.

If I may, I’d like to suggest an alternative addendum to this, and transform the phrase into: learning how to stop beginning.

I’m so fascinated by the onomatopoeic qualities of certain words, and there is no doubt that the word ‘stop’ feels and sounds very hard, harsh and abrupt - you couldn’t find a better word to represent its meaning!

If I am investing so much time in learning how to begin, why would I then want to learn how to stop? Of course, you could say I need to learn how to finish a piece/work itself, but semantically, finish is by definition more final and conclusive than stop.

For a commission and piece such as this, coupled with the approach I employed, I needed to learn how to stop beginning. To stop making, creating and dreaming, and to distil my response to this work.

I certainly did not need to finish, because my approach was going to include such a degree of improvisation and composing-in-the-moment, but I did need to know when to stop trying out new ideas, to allow for a coherence and focus to form in my work (it being a response to another work), so it could have authenticity as a piece in and of itself, I could feel a sense of integrity as the creator

Postlude

It is important to note this is written through the lens of my recent commission and therefore is clearly reflective of this activity, and subsequently there is nothing to say that this would ever be the correct approach, either for myself or anyone else to employ for a future project.

However, one of the things which really bugs me around creativity discourse is a general lack (maybe even fear) of sharing about process, approaches and methodologies; probably because these are less measurable and sell less books than the 57 Ways To Become A More Successfully Creative Version Of Yourself stuff.

Why? Because we all want a quick fix. Time is money (apparently). We all want someone to tell us how to do it.

But, no - we have to do the work. That’s why this post is so long. If you got to this point, well done! Putting in the work.

Remember the quote from the exhibition board earlier? It stayed with me, running round my heard for a fair amount of time.

‘Mary’s works take a long time to complete, and, in turn, also demand and repay slow looking.’

This is where I am, and I’m grateful to have found this place.

And next week, you get to hear it!

Wow. Detailed and fully invested approach. Fascinating to see this process. Way beyond where I am in my 88 key journey(!), which mounts mainly to 'comfort zone' playing, with a smattering of the art of noodling....

Patterns though. That strikes a chord. Still a 'beginner' in my reading of music (and a struggler), but the 'matching' of shapes and patterns is really quite interesting.

Thought provoking stuff Mr Walker!!

This series should be required reading for anyone aiming to be creative professionally. I wish I heard advice and approaches like this in college. Thank you Sim!