How does this painting make you feel?

Last week, whilst in London to play a show, I took some time during a wet, stormy afternoon to stroll around one of my favourite places: the Tate Modern museum.

I have a thing for modern art museums. I always tend to leave them inspired by the way many artists throughout the twentieth century through to now, have continued seeking to find new, varied and deeply personal ways of telling the story of modern times through their work. I especially appreciate work which is punchy; perhaps a little challenging, and ultimately dares to see things through a lens which refuses to shy away from an embedded sense of historically-influenced notions of conformity. An approach to making art which breaks the back of conforming to established norms because “that’s-just-the-way-it-is”.

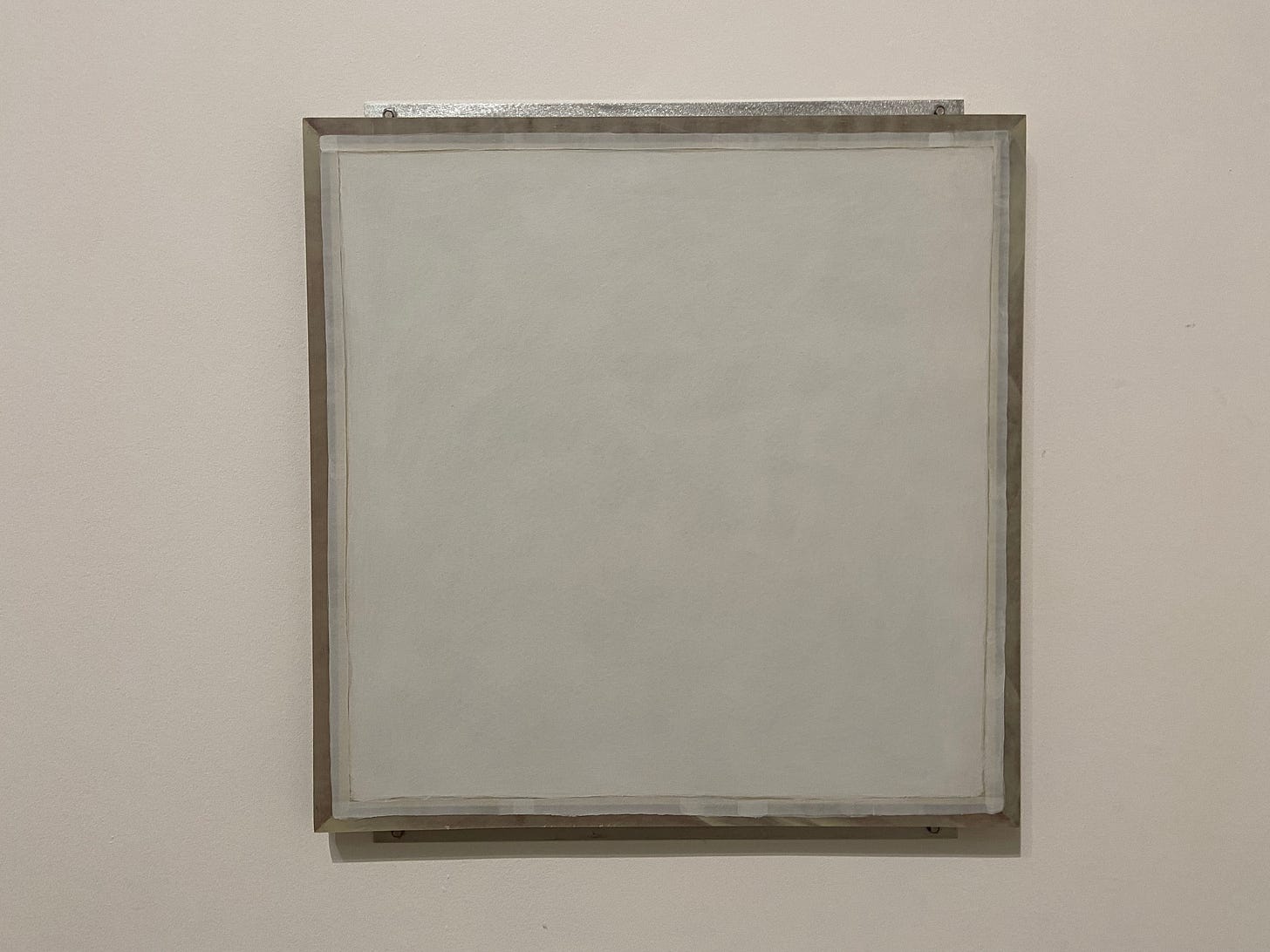

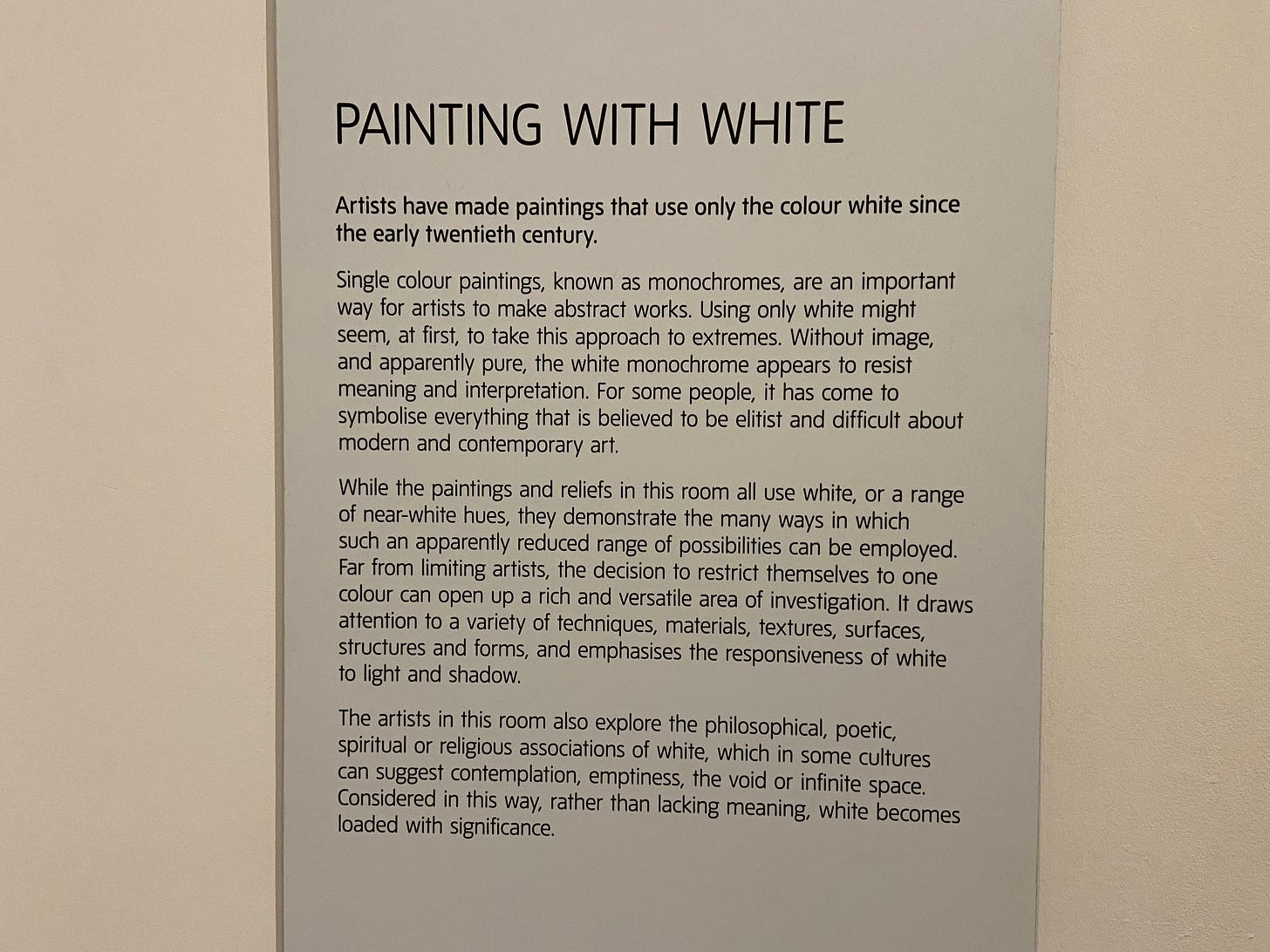

Despite the Pollock’s, the Philip Guston exhibition, and large number of surrealist works, I was especially taken with a room in which the pieces exhibited by a range of artists was titled ‘Painting With White’. Here’s the description:

Numerous elements of this short text, and consequently the works on display, resonated deeply with me. Whilst on tour this autumn, I have enjoyed sharing more insight from the stage into both the meaning behind some of my music, and the stylistic and compositional devices, aesthetic and techniques I have tried to adopt in order to achieve this.

In relation to my ‘Imprints’ release earlier this year, I made further reference to my desire to embrace spaciousness in music, which I go into more detail about in this article from a few months ago…

In a related way - and perhaps an extension of this - is a commitment to using limitation as a compositional device; in so doing, valuing a sense of restriction for its positive benefits, rather than any negative preconceptions.

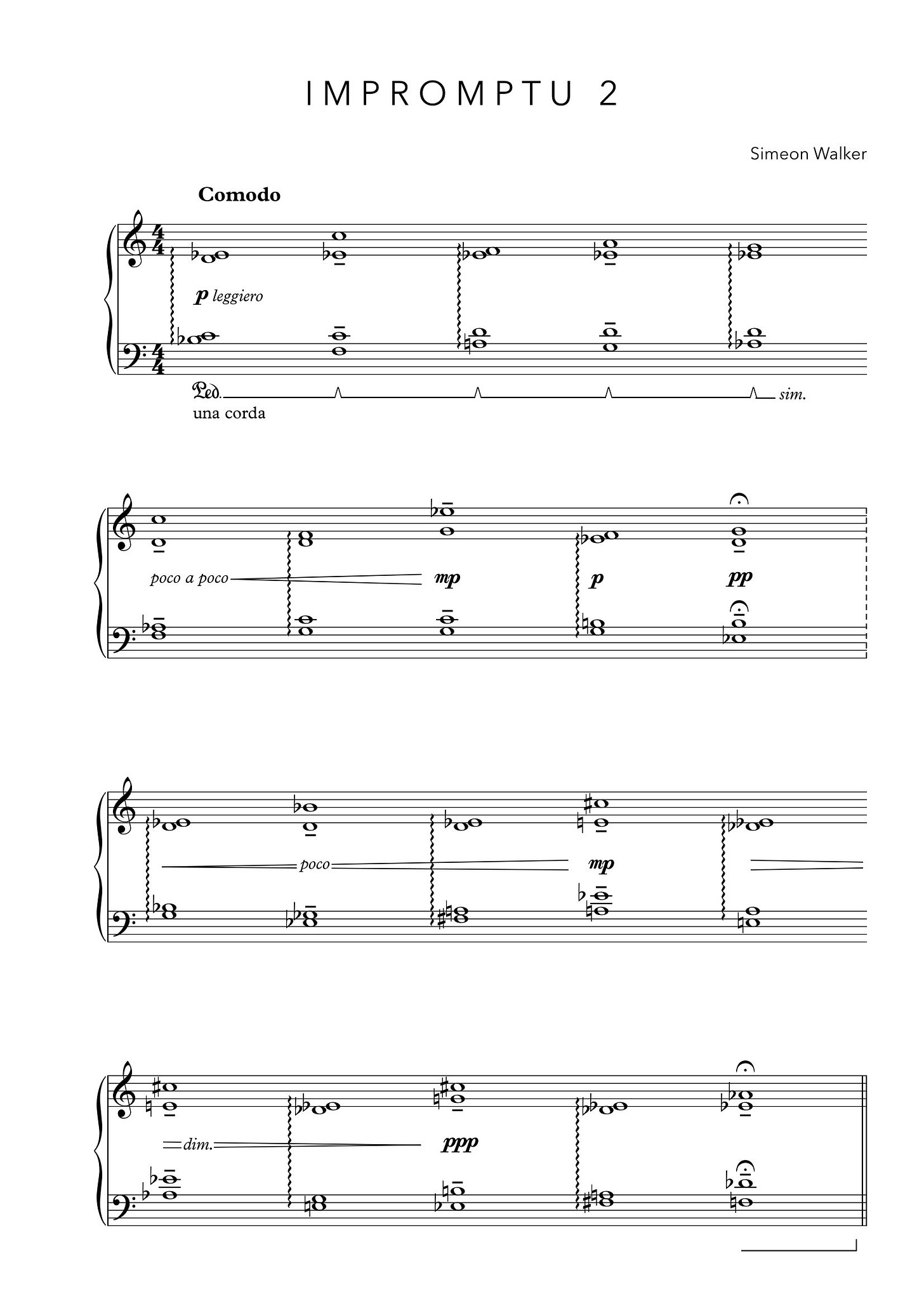

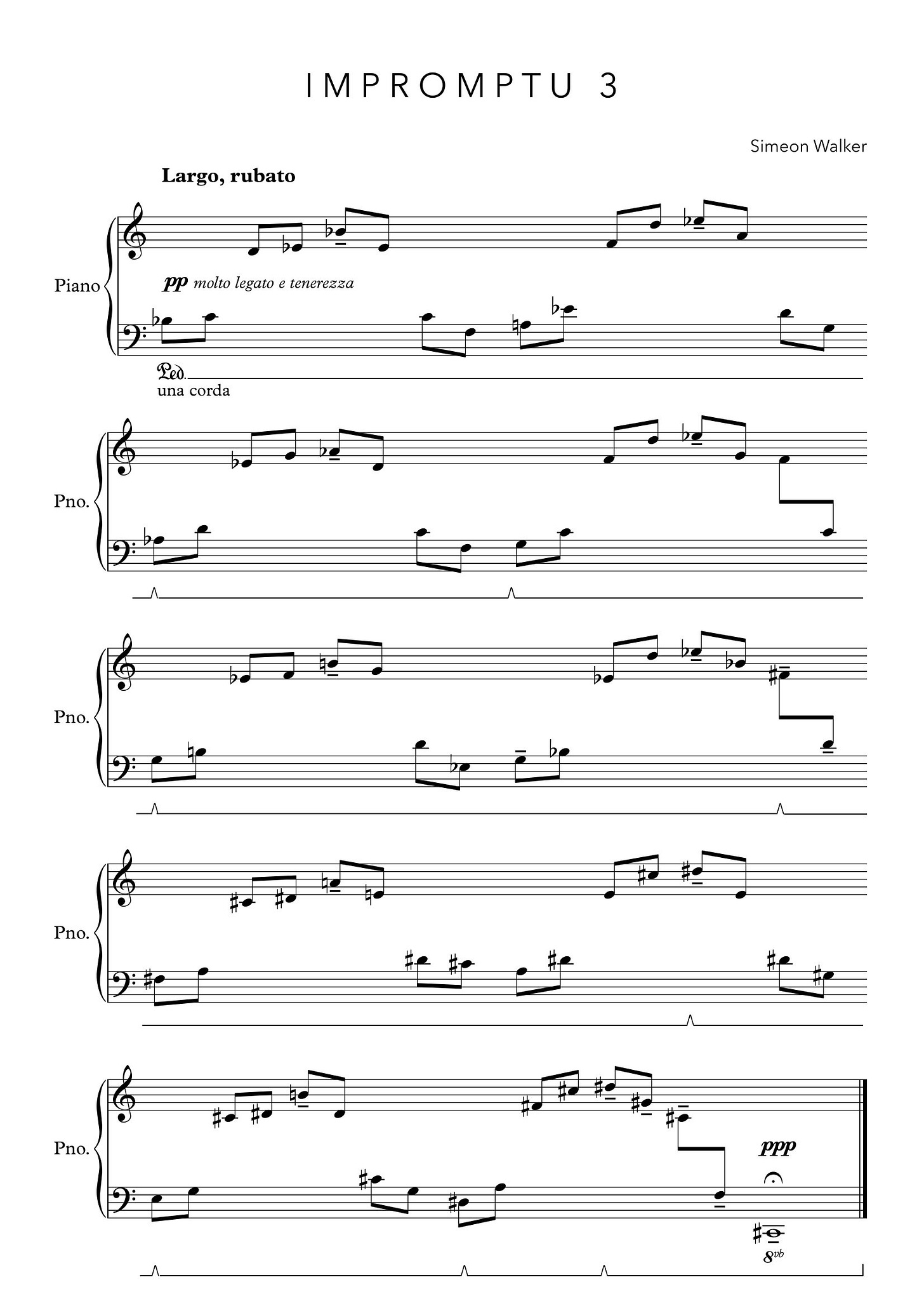

An example of this is a collection of ‘Three Impromptus’ (2022), which take on an alternative approach to theme & variation; namely that the variations are explicitly related to the differing presentation of the harmonic content in the initial Impromptu, as oppose to the more traditional development of melodic ideas. The tightly-packed chord-clusters of the first Impromptu provide the basis for the harmony of the following Impromptus:

In ‘Impromptu No.2’, the chords are varied by virtue of an unfolding of the voicings of every second cluster, creating a perpetual feeling of closing and opening, as each inversion adopts a wider, more spacious voicing, with the repetitious articulation of the first chord as a spread chord, and the second chord played with tenuti and generally slightly more withdrawn.

By contrast, the focus of ‘Impromptu No.3’ is on a rhythmical broken-chord interpretation of the previously used harmony, utilising a pleasingly wavy symmetrical pattern created by the four-note chord clusters of the original.

Whether or not you read music, I hope you can see from the score above, my desire to create a sense of openness and spaciousness can be seen in a visual way, even without hearing the music, extending as it does to removing the barlines from the music (usually music is broken up into smaller chunks of a determined length). There are a number of compositional reasons for this, but essentially it helps to visually portray how I would like the music to be heard and interpreted by anyone else who would like to play it (please do send me an email if you’d like to).

I took a similar in using a restrictive approach, albeit via a different device, in my piece ‘Paean’:

This piece uses consistent octave intervals in both hands, separated themselves by consistent intervals of a tenth throughout the piece, in an attempt to blur the boundaries between how we think of and experience melody and harmony. There is a temptation, especially in piano music, to see the right hand functioning as the driver of melodic material and the LH providing the harmonic accompaniment. In ‘Paean’, this is still broadly the case, but the limitation - or perhaps a better word is restriction - of the intervals both intra and inter-hands is the primary device at work.

Throughout this tour, I have some great discussions about this, and spoken with so many people afterwards who have asked further questions and wanted to know more about this topic. I think there is much we can learn from it; both in terms of our approach to creative practice, and as a general metaphor for the way we live our lives.

We are so often encouraged to switch off; to take time for ourselves; to aim for a better balance in our work vs. home life; to spend less time on our phones; to eat our 5 a day, get regular exercise…all of which, ironically, can become quite exhausting trying to do it all, even as a balm to the busyness of twenty-first century life. In practice, these are all rooted in trying to have a healthier, more-balanced approach to life; and it strikes me there is a greater chance of success if we adopt an approach which embraces a positive view of limitation and restriction, rather than fearing the things which might be lost along the way.

- - -

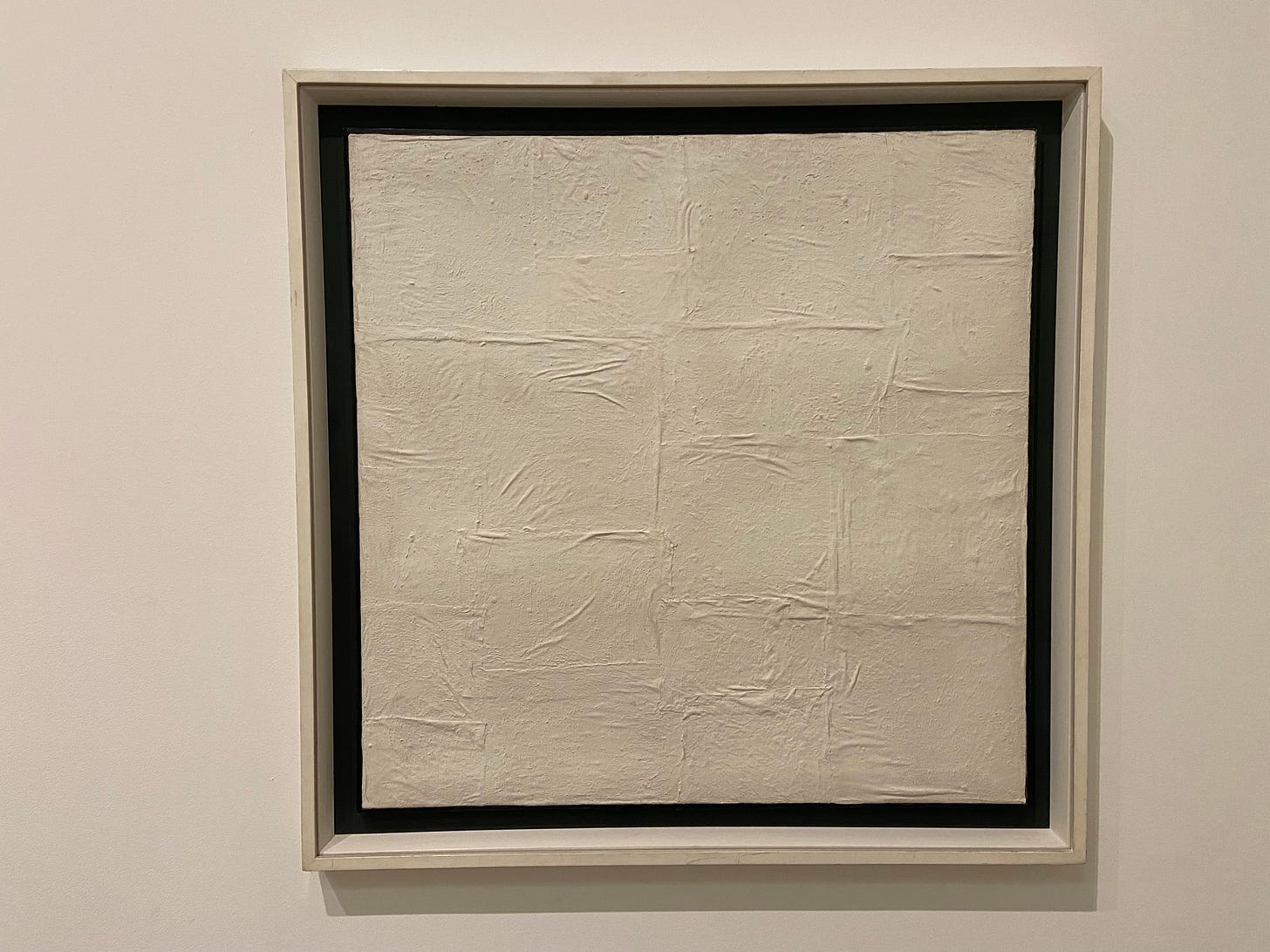

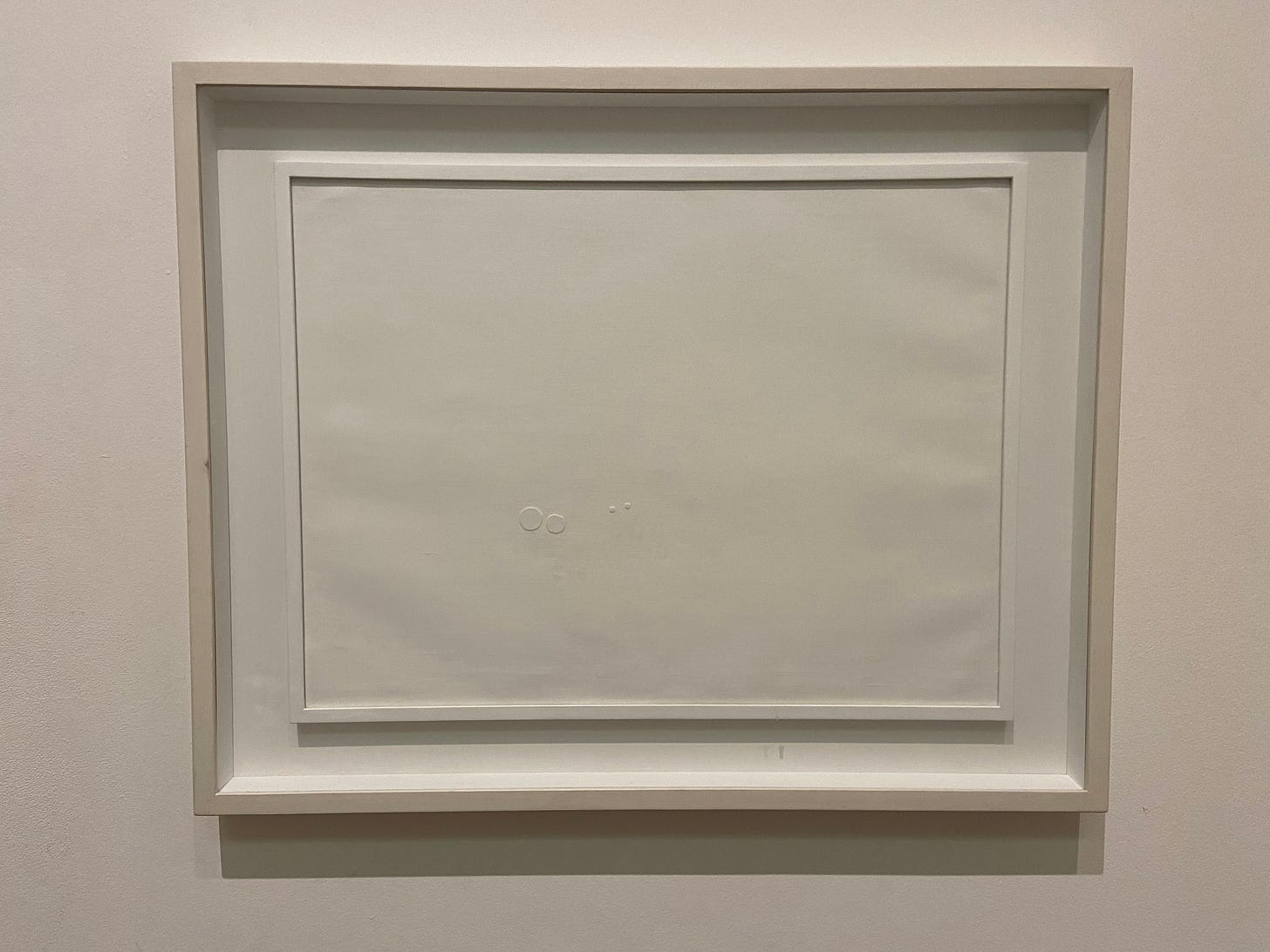

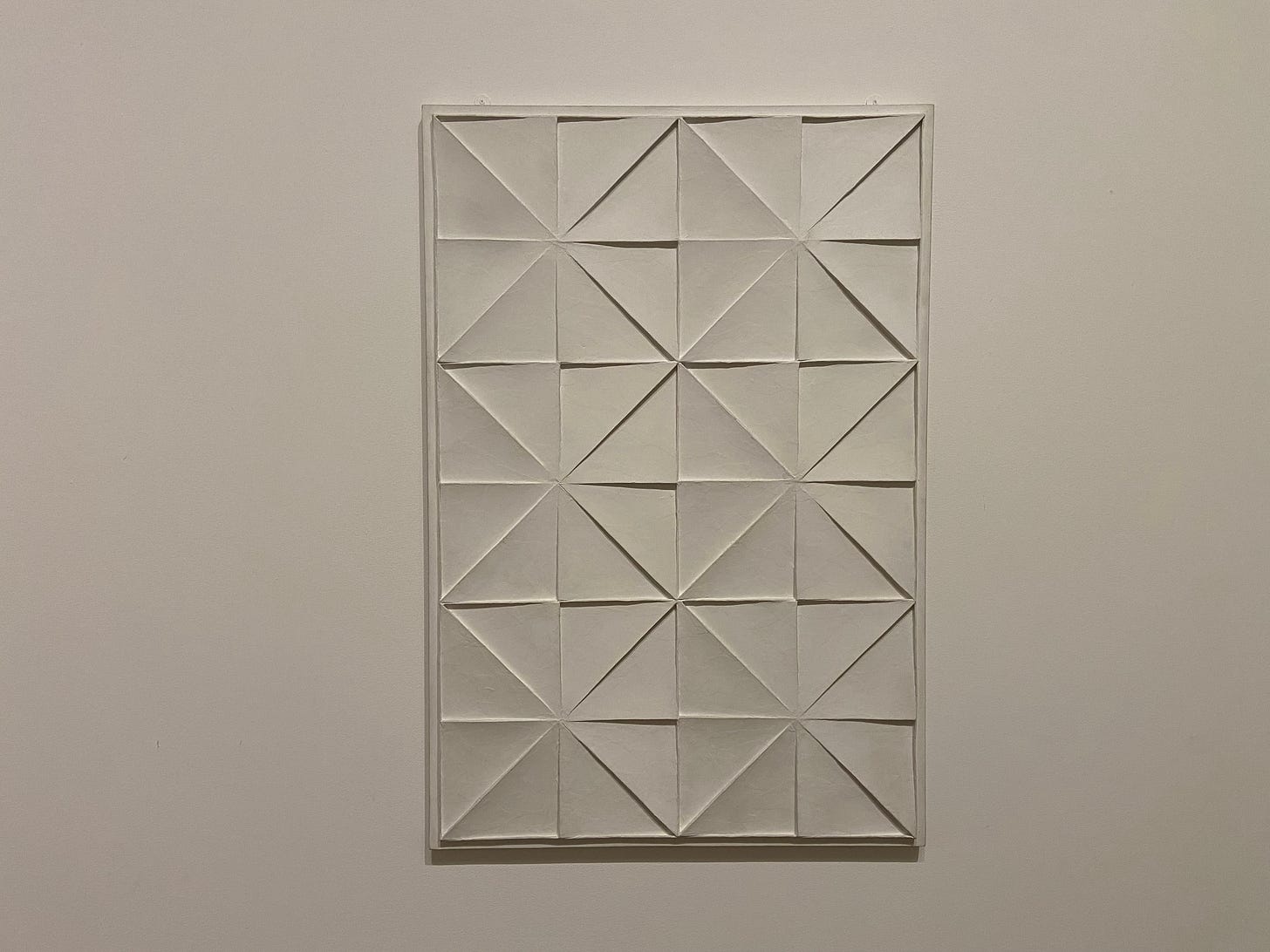

One of the things which most captivated me about the ‘Painting With White’ room at the Tate, was the way my eyes were drawn to different, surprising and less-celebrated elements of the works - texture, shape, form for example - and wondering about the different methods and techniques which must have been used to create these essential elements, but which become even more stark and apparent because of the lack and removal of colour.

In that moment, I found myself feeling encouraged and inspired, and with a greater clarity as to why I feel so strongly about this. It is tempting to see the artworks above as lacking something; feeling the absence of colour; perhaps even wondering if it has indeed been finished. Even whilst in the gallery, there were some reactions from other guests which certainly suggested some found it difficult to approach and appreciate these works.

To me, I see these pieces as being free. Free from the baggage of expectation; free from artistic convention; free from the pressure to conform to a set of rules about how artistic works should be seen; free to be.

I find it fascinating that we can so often be intrigued by the work of artists and creatives who create huge, bright, complex, multimedia webs of colour, immersion and creativity, often viewing and elevating them as the most valuable, captivating and awe-inspiring pieces of artistic experience; whilst in contrast, tending to view less bombastic creativity as somehow lesser; perhaps even simplistic.

At this point, it is tempting to trot out the usual “well, there’s a place for both” and “it takes all sorts” phrases, which, of course, is true. However, I offer this piece as a plea to see beyond the simplicity of the work discussed, and begin to wonder and attempt to understand the intention behind its creation.

- - -

In the many modern art museums I have visited around the world, Mondrian, Pollock, Rothko et al. get the glory - their work exudes a boldness with which they focus their intentions through the use of engaging colour combinations or dare I say dogmatic methodology (grid patters + primary colours; drip technique; abstraction; deep blocks of colour). But can we learn from the admiration we feel about a creative rebelliousness, one which is portrayed in a less bold, bright way? Is it possible to engage with notions of restriction and limitation in less stark, forthright ways, but which still seek to achieve similar aims?

In my experience and practice, I do not feel it is about being provocative or outlandish, and it is certainly not attempting to exude a sense of smug rebelliousness. That really is the worst. However, I feel there is something inherently freeing about the use of restriction and limitation as compositional devices (especially when self-imposed rather than dictated to by others), rather than the natural assumption which tends to see these creative disciplines in a negative light, or as an affront, even, to an open-ended, no-holds-barred, “let your imagination run wild and free” attitude which can sometimes be assumed to be the foundation for creativity.

The notion of the blank canvas, whilst freeing, exciting and brimming with possibility and opportunity for some, can become the exact opposite and enemy of creative fulfilment and progress. The age-old “where do I start/how do I begin” question will never go away, and nor should it - creativity does not always benefit from a dogmatically linear approach, not least because at the other end of the journey, the reflexive age-old “how do I know when it is finished” question book-ends our creative decisions.

When we examine our lives and the things we enjoy most, is it really the moments of pragmatism that speak to us, or is it the sense of awe and wonder - and perhaps ultimately the moments which have less conclusive answers - which give us the necessary space to breath, dream and live?

Great article, with some key 'truths' about simplifying creative processes. Limits that I also sometimes apply to photographic projects. Limit to breadth of subject, or the use of a single focal length, shoot in monochrome only, in the rain(!), etc. Results are some of the most pleasing.